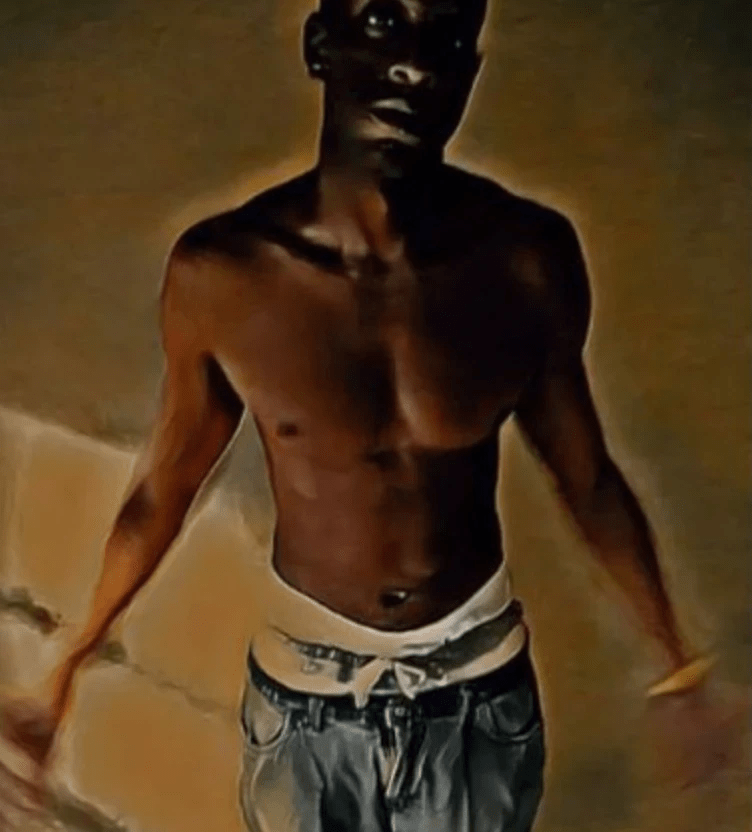

QUNTOS KUNQUEST

MY STORY

my version - their version

QUNTOS KUNQUEST

Beethoven's Piano Sonata No. 14, sitting in a prison dormitory.

My clear headphones; Skull Candy, I think. Isolating me so I can capture this moment with minimal distraction.

Captures my imagination, thoughts rattled off. Why not keep it simple and write a short bio? In 3rd person; as if someone else would care enough to speak about me. Know me so well. I mean, there are others, now. Finally.

Why? Because I'm Quntos KunQuest.

Quntos KunQuest, born 1976, in Shreveport, Louisiana. A visual artist, songwriter, and author of the début novel, This Life (Agate/Bolden 2021). He is an incarcerated artist, imprisoned since 1995, held in Louisiana's prison city, Angola, LA., properly, Louisiana State Prison since 1997.

The simplified version holds that Quntos KunQuest has been imprisoned 29 years for a carjacking. In 15 minutes he destroyed too many lives and he has spent every day since working toward atonement.

As an answer to my own truths, I'll continue to write and publish books (with help from my friends). I'll also publish music and paintings and whatever else God moves me to create. My faith being that other human beings will see value in my work. That in some meaningful way the very human impulses within the work will add something useful to someone else's life.

...That, in itself, would be validation, I believe. That no matter where our paths lead us, lived well, it's all for the glory. That, indeed, life is for the living.

ZACHARY LAZAR

In 2013, I spent a week at the Louisiana State Prison at Angola. The photographer Deborah Luster and I were on assignment to document The Life of Jesus Christ, a passion play that was being performed by men incarcerated there as well as by a group of women incarcerated at the nearby prison in St. Gabriel. Luster and I both have a parent who was murdered—both murders were contract killings in Phoenix, Arizona—and I expected to write about this fact and something redemptive about the Christ story as depicted by these actors, many of whom were serving life sent ences for violent crimes. But over the course of that week of long, unsupervised conversations, I began to feel I had more in common with some of the incarcerated people I spoke to than I did with many people I knew in the free world. Despite our other differences, we all had firsthand knowledge of violent crime and its consequences. Many of them were philosophically and spiritually inclined in ways I identified with.

Quntos KunQuest was part of the sound crew for the play and also wrote some music for it. He had zero desire to talk to me at first, but once we started talking it became clear to both of us that we have the same brain shape. KunQuest wanted to write stadium songs, he told me that first day, songs for a huge crowd, which he likened to building an outfit around a pair of shoes or a necklace, a simple central concept as the focal point of a larger composition. Eventually, we started talking about books. He had been reading Machiavelli’s The Prince, and he believed that most people don’t appreciate its depths; they just rush toward the superficial points without appreciating the nuances or the development. And, as KunQuest said, “What you do small, you do large.”

KunQuest and I started corresponding by mail—the same method we used to conduct this interview. At some point, I mentioned I was trying to write a novel about a man ser ving life at Angola, and he told me he had written a novel like that himself. The manuscript was handwritten in ballpoint pen (KunQuest had transcribed a new copy of the novel for me, all 343 pages of it), and it arrived in my mailbox in November of 2015, almost twenty years into his sentence. The action centered around the relationship between Lil Chris, a new arrival, and Rise, who has been in prison for many years, their story interspersed with vivid set pieces describing daily life at Angola, written in many registers, from the African American slang of the dialogue to the rich mix of formal and colloquial English of the narration to rap lyrics. It was dramatic, elegant, and funny—funny in a way only possible for someone who in real life has maintained his sense of humor and joie de vivre two and a half decades into a life sentence for a $300 carjacking. Six years later, KunQuest’s debut novel, This Life, is finally going out into the wider world.

JALANI COBB

It would be easy to skim the back cover of “This Life,” the vital, inventive new novel by Quntos (pronounced “QUAN-tuss”) KunQuest, glean the fact that the author has, for the past twenty-five years, been incarcerated at Angola prison, in Louisiana, for a carjacking committed when he was nineteen, and presume that the book belongs to the genre of prison literature predominantly concerned with exposing to the world outside the horrors of the one within. There is a significant nonfiction tradition of these books. Piri Thomas’s “Down These Mean Streets” and “Seven Long Times” dealt with how incarceration effaces the humanity of its subjects. Sanyika Shakur’s “Monster,” which recounted his years as a Los Angeles Crip and his multiple stints in prison, graphically described routine violence and sexual assaults in the system. And Piper Kerman’s memoir, “Orange Is the New Black,” illustrated the material and moral costs of the war on drugs.

That Angola—a facility that began as a slave plantation—was the setting for another recent book, Albert Woodfox’s “Solitary,” a sprawling memoir of the decades Woodfox spent in solitary confinement, is even more ballast for suspicions about what “This Life” has in store. But part of what makes the book memorable is the fact that KunQuest—perhaps because he’s working in a fictional mode—is concerned with a wholly different and more subtle set of questions. “Once you’ve been in the fire for so long . . . you get used to the heat,” he told me recently, when we spoke by phone. “Once you get used to the heat, you start living, man.”

illustration Joe Gough

EASY WATERS

A life sentence in prison is life, that is, there is living to do in prison, even under a life sentence. Quntos KunQuest, in his novel, This Life, demonstrates that life goes on inside of prison. Since 1996, KunQuest has been living, and writing, in prison.

I have a long history and engagement with writing and writings from prison, with “prison literature.” For a number of years, I volunteered with the American affiliate of PEN International, the writers’ organization, PEN America, in its Prison Writing Program (PWP). As a poet, I sat on the subcommittee that judged poetry submissions from people in prisons and jails from across the nation for PEN’s annual Writing Awards contest. I, myself, have garnered seven PEN Awards, and four Honorable Mentions, in poetry, drama, and nonfiction.

Writers and aspiring writers in prison would submit their works to the writing contest. Aspiring writers often begin with poetry and soon, as John Steinbeck wrote, discover that it’s the most demanding form of writing, and move on to the short story, another demanding form of writing, and finally settle on the novel. Nonetheless, poetry was and continues to be the most submitted to category for PEN’s annual awards contest. Much is awful religious and love poetry.

In This Life, KunQuest is by terms poetic in his prose, though it is informed by Rap and Hip-Hop culture. (The book, itself, is divided into “Verses,” not “Parts.”) KunQuest is a “musician, rapper,

visual artist and novelist.” Note that KunQuest is not described as a poet, which bears mentioning, because there is a fine distinction between a rapper and a poet.As I read This Life, it struck me how music deeply informs Black culture, wherever Black people are, on the plantation, or in the penitentiary. KunQuest, born in 1976, the year America celebrated her 200th birthday, is deeply informed and formed by Rap. As one of the main characters, Lil Chris, KunQuest’s alter ego, or better yet, a composite sketch of young Black men, goes through the

brutal prison rite of passage, one sees the evolution of his Rap, from signifying about life on the streets in the Game to a more elevated social commentary, looking at the streets and how they serve as a pipeline to prison, the ultimate social control mechanism. This social commentary critiques and deconstructs the prison-industrial complex and hyperincarceration (what we call “mass incarceration”), and the forces that led to the United States locking up more people in prison than any other nation in the world, and holding them for longer periods of time than any other nation in the world.People writing from American prisons, from the very beginning of this uniquely American experiment, critiqued the prison system, as documented by James McGrath Morris in Jailhouse Journalism: The Fourth Estate Behind Bars. These critiques have made it to the Academy as well as PEN America. A number of years ago, my colleagues and I participated in an American

Studies Association Conference panel we proposed, which was a presentation to argue “prison literature” into the canon of American literature. And I recall conversations with members of the PWP Committee, where I articulated that I believed there was a writer somewhere in prison in America who was laboring over what could be the next “Great American Novel.” I don’t think my fellow committee members were convinced of this, nor am I suggesting that This Life is that novel. But This Life must be added to the canon of “prison literature.” The author Rachel Kushner writes that “KunQuest has dreamed up, molded, hammered, and shaped a new mode of fiction: American, poetic, wonderfully free.”From reading thousands of poems from prisons submitted to PEN’s annual writing contest, one would dig through a lot of rubbish, but would ultimately come across all kinds of jewels. I would hazard a guess that there are jewels among all the other categories, even more remarkable

in that the overwhelming majority of people writing from prison have no formal training or education as writers. They have had to forge their craft in the fires of prison. In fact, as Jimmy Santiago Baca, award-winning poet and educator, writes in an essay, “Coming Into

Language,” in PEN’s anthology, Doing Time: 25 Years of Prison Writing, edited by the late Bell Gale Chevigny, a former Chair of PWP, people in prisons who have taken up the pen have had to emerge from the darkness of illiteracy into the light of literacy.In This Life, KunQuest illuminates a cast of characters – to name a few: Lil Chris, Gary Law, No Love, and Mansa Musa – as memorablecas characters in the best of fiction, including one of my favorite

characters, Edmond Dantes, from The Count of Monte Cristo. Though Alexandre Dumas’ novel is not thought of as a tale of crime and punishment, of reentry and reintegration, it is. It is also a

coming-of-age story, in prison.

One of the tragedies of the American penal system, is that, as Norman Mailer discovered when he was researching and writing The Executioner’s Song, and wrote in his introduction of Jack Henry Abbott’s In the Belly of the Beast:

There is a paradox at the core of penology, and from it derives the thousand ills and afflictions of the prison system. It is that not only the worst of the young are sent to prison, but the best – that is, the proudest, the bravest, the most daring, the most enterprising, and the most undefeated of the poor. There starts the horror.

Out of the horrors of the prison system, in spite of, not because of, these proud, brave, and daring men are forged, only to languish in prison for their natural lives or the best years of their

lives, only to die shortly after their release.Rise, one of the main characters in This Life, who is ultimately released through a successful petition to the courts, gives an orientation to the new arrivals at Angola State Penitentiary, a

former plantation, nicknamed “The Farm,” in West Feliciana Parish, Louisiana, the setting for this story. He quotes Marcus Aurelius’ Meditations, comparing God to a blacksmith. “We are the metal. The fires of the furnace are the trials of life…. The things we go through in life are

what shapes us to become the people we are.”What has shaped Quntos KunQuest? What has shaped This Life?

In reading This Life, one will encounter real life characters and leaders who could give master classes on Constitutional Law, Civics, and Philosophy. They are Lil Chris’ (KunQuest’s) mentors.

Despite the prospect of living their lives and dying on The Farm, these characters find purpose, and become conscious of the “infinite potential…of… [a] constantly evolving lifespan.” As a society, we must redeem these lives. Any outstanding debts owed to society can be paid

through their contributing their talents to society, not spending the

rest of their lives in prison.https://ezwwaters.com

ACCOLADES

HURSTON/WRIGHT LEGACY AWARD, 2022 The Hurston/Wright Legacy Awards program honors Black writers in the United States and around the globe for literary achievement. Introduced in 2001, the Legacy Award is the first national award presented to Black writers by a national organization of Black writers. The Legacy Award is awarded to published book authors in the categories of Fiction, Debut Fiction, Speculative Fiction, Historical Nonfiction, Memoir Nonfiction, and Poetry. Former Legacy Award finalists and winners serve as judges for the Legacy Awards.

GET TO KNOW MY WORK

CRITICAL RESPONSE

(add) reviews of This Life

SUPPORT MY WORK WITH A TAX DEDUCTIBLE CONTRIBUTION

100% of what Justice Partners's receives will go to support Quntos KunQuest's work

STAY IN TOUCH

Get notified of new drops & news.

Justice Partners, Inc. a 501(c)3 is a fiscal sponsor for Quntos KunQuest's storytelling development